The Film

The initial seeds of this film are more than a decade old. In 2007 Emma Findlen LeBlanc and Phil Sands were on assignment for GQ Magazine in Iraq, embedded with the 101st Airborne Division in the “Triangle of Death.”

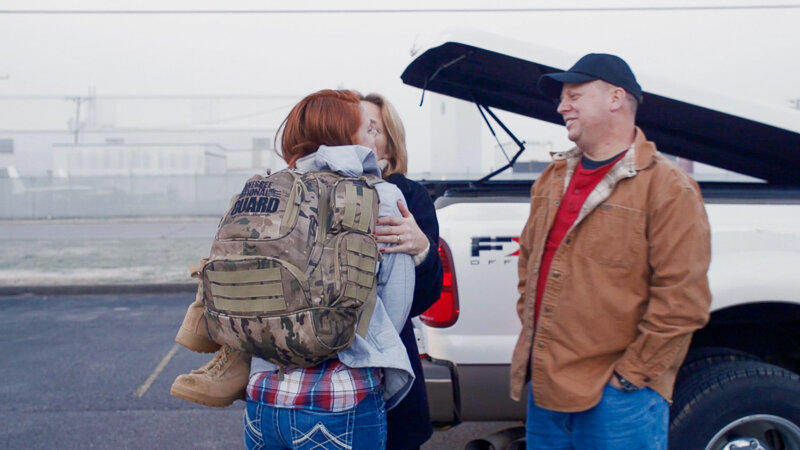

They stayed in touch with some of those soldiers over the following years and the soldiers’ reflections often slipped into a complicated nostalgia for Iraq, a longing muddled with anger and loss. Combat was hard, but in some ways, homecoming was harder. PTSD and physical traumas were the obvious difficulties, but there was also the challenge of readjusting to a civilian life that would always seem mundane and directionless compared to the razor-sharp singularity of life in a war zone.

As one of the officers put it, “Odysseus is okay as long as he never sets foot in Ithaca. But what happens when he comes home?”

Homecoming is a process that lasts years rather than months, as a liminal space one inhabits indefinitely, as a simultaneous, overlapping yearning and anger and guilt.

The film focuses on combat medics, because theirs is in some ways the most extreme experience, both of war and of homecoming. They see the very worst side of conflict. Their world is populated by the wounded, the dying, and the dead. They never get to look away. But they also save lives, and their importance — their sense of meaning and purpose — is unmatched.

IF YOU CAN EVER GET BACK seeks to tell a harder, more complicated story of the Iraq war, honoring the complexity of the films’ subjects, who defy the comfortable stereotypes of veterans as heroes or victims.

We hope to offer veterans an honest depiction of their experiences, and to challenge those outside of war and its effects to reconsider their assumptions. The staggering candor of these medics challenges the polite public narratives of America’s post-9/11 wars, and defies the usual postures of toughness soldiers mostly muster for one another. We offer no easy answers, only an insistence that we must reckon with the ongoing consequences of our most recent and ongoing wars. These are age-old, essential human questions — what it means to kill, the value of a life, the cost of war — with urgent implications today.